What makes a candidate “good”?

Or at least, what is an indicator of “goodness” we can find in election data?

The obvious answer is “did they win”, but this is a pretty limited metric. There’s a huge difference between running in a long shot R + 10 seat and running in a safe D seat, and the same candidate might lose terribly in one but do great in the other, with no reflection on their personal performance. Plus, we want people to run in those longshot seats just in case the national trend shifts and we have a chance (see my tipping point piece).

The next possible metric is “how they did compared to something like the presidential”. This has the useful feature of being really easy to calculate. In theory, doing better than another Democrat in their same district would be the mark of a “better” candidate. You could compare to any other election in the district, I guess, but usually people use the presidential because it’s cleanly partisan, and since it’s national you can compare many different candidates to the presidential result in their district.

[NOTE: I’m going to be relying heavily on Split Ticket’s data throughout, because it’s nice and also easy to access. Thank you Split Ticket, everyone go check out their excellent website. ]

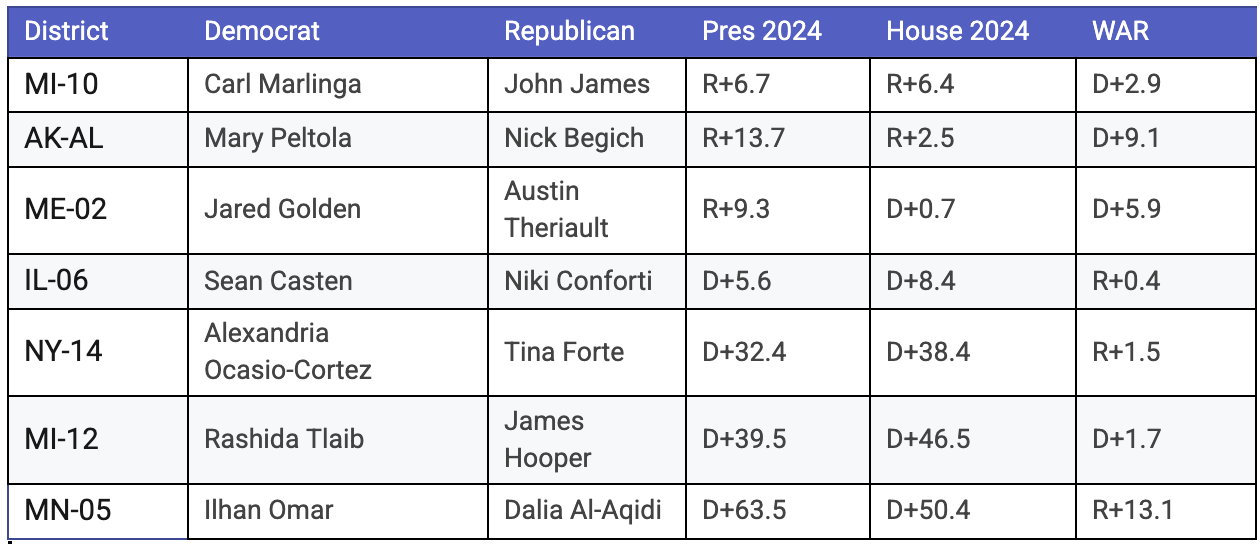

Anyway, here are some house seats.

These are nonrandom, but I did try to get a decent selection. You’ve got a couple of really heavily Democratic spots, a couple Republican ones, and some in the middle.

Let’s start with Sean Casten of IL-06. He’s got a House margin better than the presidential, by a bit. Is this impressive? It’s hard to know in isolation!

Here’s IL-06 compared to the other IL House seats for which there were two candidates (a couple were uncontested). That orange triangle is IL-06, and the diagonal line is marking where seats with perfectly identical House/Presidential results would be. IL-06 is slightly above the line, but so are several other seats.

Here’s that same thing for NY. There are a ton more seats where the House margin was better than the Presidential one, and I have similarly highlighted NY-14, AOC’s seat.

Is this an indicator of truly exceptional candidates running across NY? Nope, you can quickly dismiss that by looking at previous years where they mostly underperformed the Presidential.

Instead of being a result of individual candidate quality, this tendency of NY congressional candidates to run ahead of the presidential is a result of structural changes in the NY electorate and how the state votes. Presidential results for Democrats absolutely cratered in NY, as I noted in my immediately post-election post, and this meant that suddenly congressional candidates were being measured against a much, much worse Presidential number. This trend doesn’t seem to have hit House candidates as much just yet, so they all have relatively strong overperformance of the Presidential. “Being in a seat where the presidential numbers cratered” is not an indication of being an amazing candidate, and doing the simplest comparison alone can trick us here.

Beyond Presidential Comparisons

Returning to our set of example candidates, we can see that just presidential vs house numbers doesn’t tell us a whole lot. If we want to get a better sense, we should probably be accounting for how well they did compared to both the presidential and to the other candidates in their state, which would allow us to handle that NY situation. If we want to be fancy, we could also control for things like “being an incumbent” (generally really good for your electoral prospects), “raising a ton of money” (useful on margin, not a magic bullet), and even “type of district” as described by demographics. These factors, as well as past election results in the district, make up a baseline to which you can reasonably compare the candidate.

I do not personally have the time to be fancy, but the folks at Split Ticket did. Their Wins Above Replacement model is quite good, and takes into account all the factors I described above.

To be clear I encourage anyone interested in using these candidate quality measures in their work to try re-deriving something like the WAR model and tweaking the inputs. I think that’s more informative than relying on a single model that you aren’t familiar with the inputs of. Plus, I’m not entirely sold on including fundraising numbers in a model like this, since I tend to think of them as partially downstream of candidate quality. But if you’re short on time (hello), the Split Ticket model does basically what I’d want this kind of tool to do.

Looking back at our sample candidates, we can see the WAR metric varies a lot. MI-10 had a candidate slightly overshoot the presidential, and put up an impressive performance compared to baseline, but still lose. AK-AL had my fav Mary Peltola (pro fish forever) do a similar thing, with a much more impressive WAR, and just not quite be able to beat the national R trend.

ME-02, Jarden Golden, is a good example of a seat where candidate quality seems to have made the difference between a win and a loss. He significantly improved on the Presidential trend in his district, and kept the seat.

Down in our more Democratic districts, we’ve got a mixed bag. AOC (and many other NY candidates) put up a depressing WAR, despite staying slightly ahead of the sliding presidential numbers. This isn’t a huge problem for a candidate in a deep blue seat (she still won by a lot), but it would be a massive problem in a swing seat. Ilhan Omar has a similar problem. Tlaib is the opposite, putting up a small but respectable WAR despite being in a very very blue seat. It’s not inherent that candidates in deeply blue seats will have poor WAR, it’s just that these safe seats are more tolerant of candidates with mediocre performance compared to fundamentals. Being a few points behind baseline doesn’t matter if your district is D +50.

We can measure it, but what IS it?

The above results by candidate show that some candidates do better than expected of a generic candidate, some do worse than expected, etc. But it doesn’t really tell us much about why this happens.

A complexity here is that elections are fundamentally contests between two (or more than two, but I’m ignoring that because it makes everything more complicated) candidates. An overperformance by one candidate might just be because their opponent is a total screw-up, or barely campaigned, or got arrested, whatever. Sometimes you can pick this up via smell test, googling the election and seeing if there are any obvious gaffes happening. It also shows up in fundraising, where tragically small amounts of fundraising can indicate a not-very-serious campaign.

One way to mitigate this is to look at WAR scores by the same candidate over time, as they run against a variety of opponents. This is also complicated, since being an incumbent is such an electoral advantage, but it helps. If you do this, you’ll see that candidates who overperform once tend to keep doing it. This makes me feel a bit better about treating candidate quality as something belonging to the candidate, and not just an artifact of the particular contest.

Some parts of “candidate quality” are super obvious. Not getting arrested is probably good for your campaign. Having enough money to run is important. Not literally dying on the campaign trail seems to help. Others are mushier- being a “good speaker” seems helpful, and while I can identify compelling speakers when I hear them I’m not sure I can measure that. “Charisma” is a similar thing.

I think a lot of left-leaning folks, when discussing candidate quality, can become worried that we’re determining there’s a certain type of person who is “best” at being a candidate, and that this might exclude minorities, women, simple non-charismatic people, etc. Luckily, this isn’t really what candidate quality describes. The research on penalties for women and minority candidates is actually really encouraging. It seems like when women run, they do just as well as men. Similarly, minority candidates do not seem to face a penalty in election results. There’s some interesting factors going on in primaries, where voters maybe prioritize white male candidates due to electability concerns (driven by exactly these misunderstanding of how those candidates would perform in a general!), but in general elections it doesn’t seem to hugely matter.

What we’re mostly measuring here are choices the candidate made. Things like being well known locally via running a local business, being on the news, being in a different political office, can all really help. Simply increasing local awareness of who you are does a lot. If an uninformed voter looks at their ballot and goes “hey, that guy!”, you’re probably gonna do okay. Effectiveness of your campaign also shows up in candidate quality measurements. Things like ability to do interviews, hold events and shake hands and so on. This is where Biden really struggled, and it clearly hurt him.

Heterodox Moderation

The other major thing that seems to impact candidate quality is matching the views of your constituency. This sounds ridiculous- of course candidates do this- but is imo underrated. Peltola in Alaska talking constantly about loving fish and also guns clearly helped her a lot, because those are things important to Alaskans. Some of my very local candidates will talk about how much they hate the rental market and love gardening. Jared Golden is anti offshore wind for lobster reasons, and has many specific fish-based opinions, in addition to taking a fairly R leaning stance on tariffs. Even a very ordinary person can increase their candidate quality by looking at what their constituents like and believe and echoing them. This is why I am so pro moderation via heterodoxy. We have got to give our candidates the freedom to do this sort of position taking, match their constituents, and improve their own candidacy.

The increased nationalization of politics has made this harder, as now even locally-focused candidates are looking out for donations from a national donor population. The sort of Democrats you end up targeting with a small donations program (via ActBlue, texts, whatever) are disproportionately college educated, urban, and likely to donate to many candidates over time. They’re also more left than the average American. This is a weird incentive structure- you need the money to run, but donors want more left statements than your constituents do, and suddenly you want favorable coverage by Democratic leaning outlets that might actually hurt you in the election. I have some really fun data on the surprising continuity of donor populations across candidates and over time, which is a subject for another article and requires me to put a database back together. Later.

With the sheer amount of money in Democratic politics these days (the Harris campaign spent over a billion dollars), I think it’s easier to encourage candidates to opt out of this trap. There are good organizations ensuring that candidates who don’t compete for mainstream donation attention are still funded, and being in an even slightly close seat will get you $$ funneled to your campaign by strategic actors. For the average candidate looking to improve themselves, I’d suggest shaking hands, going on TV, and trying out some not traditionally D coded positions that match your constituents. Odds are, you’ll get a little negative news coverage, which will actually improve your name recognition and support with your voters. Someone might tweet about you. Is this unpleasant to go through? Probably, this is why I am not ever running for office. But it’s good for you, and if you’re running for office, you should either have or develop the thickness of skin to take it. It’s a bit like the veggies of running for office, and you can probably learn to appreciate it.

I am fully supportive of “moderation through heterodoxy” but I worry that there are limits to this in today’s media environment. It may just not be feasible for local candidates to make significant headway against the nationalized impression of their party created by social media. If anything, Republicans may have adapted to this better by having a centrally controlled national brand, and dems should be trying to find some way to do *that*.

great read