Does running extreme candidates increase base turnout?

A review of academic literature, concluding “maybe a little but probably not such that it matters”

Turnout in the context of political practitioners can mean two things. On one hand, it can mean running explicitly GOTV programs, or voter registration programs. These are proven to increase turnout, if by a small amount. While there isn’t certainty about the upper limits of these programs, they are a concrete thing that works. They’re also not really what I’m interested in for this review.

The second thing is what you might call “base turnout” or “rallying the base”. This is less about turning out specific voters (although it is implicitly targeted to partisan Democrats) and more about increasing the total turnout from your base. Base turnout is generally presented as an alternative to working to persuade swing voters or marginal voters to select your candidate over your opponent. This is what I’m most interested in, because it presents a significantly different strategy than focusing on swing voters.

Most specifically I’m interested in the question of “do more extreme candidates actually rally their base?”. Since this is being written from a Democratic strategist perspective (hi), I am functionally interested in do *Democratic* more-left candidates rally the base?

To set terms, the effect I’m looking for would look like on average, candidates who are more to the left producing higher turnout among Democrats. The magnitude of this effect would have to be larger than either 1. Increased turnout among Republicans or 2. Vote switching by swing voters away from the Democratic candidate.

What does “more to the left” mean?

I’m defining this as candidate ideology as expressed by metrics like DW-NOMINATE, CFscores, or other methods. These are the most “objective” metrics out there, and they also tend to be applicable across lots of candidates across time. I know that every time you talk about “more extreme” candidates online people start explaining to you why their politics aren’t actually extreme, and I’m not gonna mess with that here. Extremism isn’t a moral judgement, it’s a statement about their relative positioning in the field of candidates. I worked for Elizabeth Warren, I am not out here being like eewww extreeeeeeme.

There’s a whole separate issue that different measurements produce different results by candidate, and some (DW-NOMINATE) are increasingly unworkable in modern politics. That’s outside the scope here but it is interesting if you want to look into it.

What about persuasion?

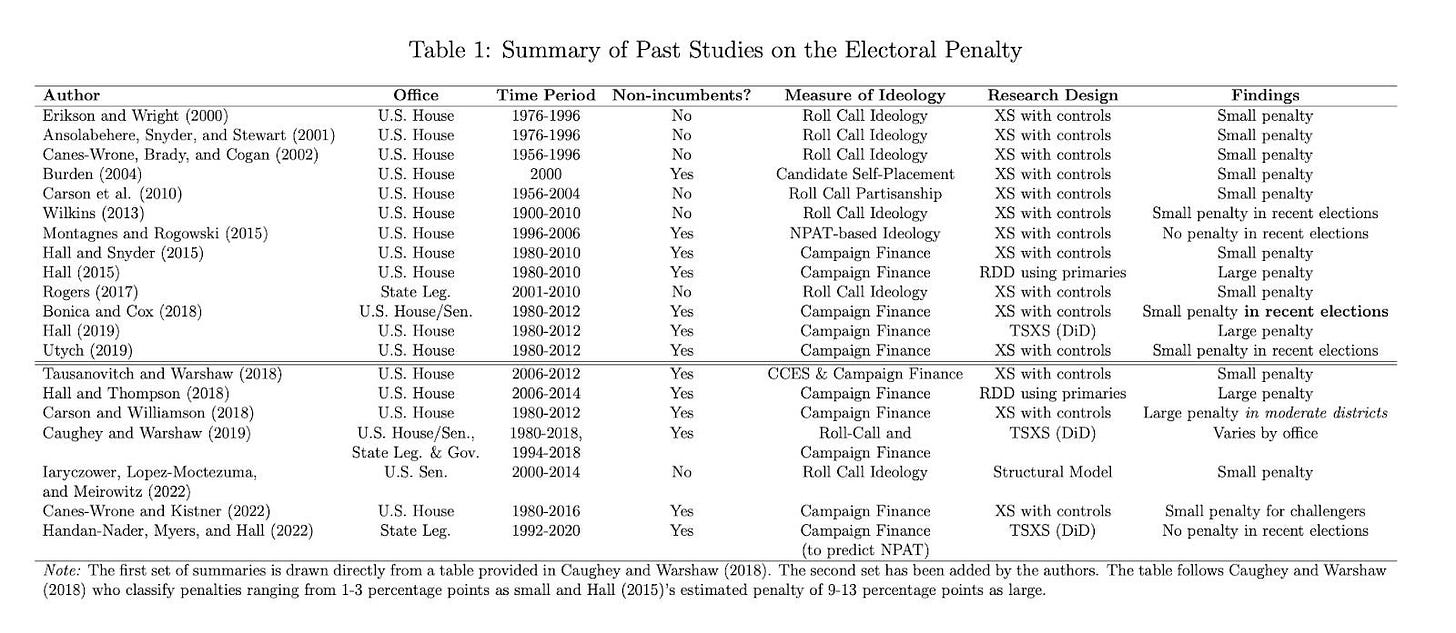

Per that rad summary chart in the Bonica paper I wrote about recently, the literature on the electoral penalty to extreme candidates is pretty well established. It seems to indicate a small but meaningful penalty, with some uncertainty about recent elections and dependency on how exactly you measure ideology. I feel confident saying that an electoral benefit to moderation exists. I also have the sense that this is less controversial among practitioners of Democratic politics. Instead, the concern seems to be that there is a counteractive turnout effect that would erase any gains from moderations. Hence the focus of this review.

The State of the Literature

My overall impression is there is not very much literature specifically addressing turnout effects of candidate ideology. This is pretty surprising given how large a role this concept of base turnout plays in modern politics! Some of this may be that it’s incredibly difficult to run this sort of analysis without access to a voter file, which can be prohibitively expensive. I suspect more analysis has been done privately in Democratic spaces and then not been shared. While I totally understand wanting to keep a close hold on strategic research, at a certain point, it would be really useful to help the public update their knowledge.

[The list of papers I reviewed is at the end of this piece]

Again I am not an academic and it’s going on 10 years since I was a student of political science. I did ask for some help on this (thank you academic friends, appreciate you) to get a better survey of the literature. One note if you’re trying to follow up here, most papers use “composition” (as in composition of the electorate) instead of “turnout”. This is a more accurate term which I may adopt, since “turnout” can mean aggregate turnout or turnout by a given party.

Womp Womp, Measurement is Hard

One challenge is that there are just not that many “extremist” nominees. The problem with election research is constantly that you don’t have very many datapoints, which you can somewhat mitigate by using the entire US house or state legislative elections. Even with that expanded scope, there really aren’t that many candidates who are notable to the left or right of the average. This may not match the sense you get from twitter, but it’s genuinely pretty uncommon.

This paucity of datapoints lead to a revision of one of the papers most directly addressing the turnout effects of extremism. Hall and Thompson (2018) ran a regression discontinuity design (i.e. looking at places where extremists narrowly won or lost primaries) and found a large negative effect of extremism on vote share and turnout. In 2025, they presented a revision, noting that the places where extremists won primaries had recent significant drops in presidential vote share, and that this threw off their analysis. When they re-ran correcting for that effect, they found much smaller and often insignificant results on turnout and vote share. As an outcome, “extremists win in places where party vote share recently dropped” is *weird*. On twitter when this came out, folks proposed theories including damage to local party infrastructure, but I’m inclined to pin it on just random chance with a small n of extremists.

The upshot is that Hall and Thompson no longer provides strong evidence either way, and reinforces the difficulty of using RD designs. I really wish they’d redone more of their paper, frankly. The findings on turnout effects among in-party and out-party are the most useful piece, and they aren’t addressed in the revised paper. In the original paper, they specifically found increases in out-party turnout in response to extremist nominees, and marginal increases in in-party turnout that were effectively dwarfed. I would love to know if either (or neither) of those findings hold up under the correction.

Turnout vs Swing Sources of Change

The most useful papers I found are Hill 2017 and Hill et al 2021. The 2017 paper is using a *profoundly* clever design of looking at precinct level election results and voter file records of who exactly voted. He’s able to look at how many voted in both elections under review, and how many voted in one or the other, and use a model to predict these features. Here’s an example precinct with estimates from his appendix:

This is incredible? I really love this design, and this chart of estimates is precisely the sort of thing I am interested in. One issue with the paper is that it is limited to Florida 2006-2010. This isn’t really a problem with the design, but it does make generalizing the findings more complicated. Every state is unusual in its own way but Florida especially so.

He’s looking at vote switching and composition of the electorate. I struggle a little with GOP/Dem proportion of the electorate as a composition outcome, because the conclusion “Dems do better when more Dems vote” is pretty obvious. However in this case, he’s able to isolate the effect enough that I feel okay about it. The ideology metric here is midpoint as described in Bonica’s work- so we can’t draw conclusions about *The Democrat* moving to the right or left. We can try to back out the effect of the ideology of the race on average moving a given direction, which is at least related.

He finds that as the contest midpoint moves right (i.e. either the D or the R or both move right), R vote share drops. He also finds that the effect on composition is smaller than the effect on switchers, and that the effect of spending advantage on composition is large. The midpoint measure makes this tricky, but we can plausibly say that a race becoming “more extreme” in the rightward direction shrinks vote share. The spending/composition piece is interesting, since it indicates that spending advantage increases your party’s turnout more than it convinces switchers to move to you. I would guess this varies a lot based on the specific race and what kind of ads they’re running.

So: Changes in midpoint ideology affect swing more than composition, and spending affects composition more than changes in ideology do. I.e. increasing the distance between candidates does bring benefits in vote share.

Helpfully, Hill and coauthors released a newer paper using a similar design in 2021, that analyzes 6 states (Florida, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, Ohio, and Pennsylvania) in 2012-2016. This paper finds that the changes in composition alone are not sufficient to explain change in vote share, and that switchers are likely driving more of the variation in most states. Georgia and Nevada vary from this pattern, showing a larger effect of change in composition.

From the paper,

“we also find that in four of the six states, composition and conversion favor different candidates. Conversion effects, however, are more often in the same direction as electoral change”

The 2021 paper doesn’t tackle the effects of candidate ideology on turnout/composition, but it does give us a check on the possible magnitude of a composition effect. If change in vote share is better explained by switcher behavior than pure composition, anything that primarily affects composition will likely be drowned out by switching. The takeaway, as I understand it, is that change in candidate ideology likely affects switchers (or “conversion”) more than change in composition (“turnout”), and that switchers have a larger magnitude of effect across most races studied. These effects are frequently in the same direction, but there is variability by state.

I found the 2017 and 2021 Hill papers to be basically in line with my thinking that a turnout based effect in the opposite direction of a persuasion effect seems unlikely. I’m not super confident in that conclusion, because detecting something that should be definition cancel out is hard, but that’s where I am landing.

“Securing the Base”

The most explicit attempt to measure the effect of “base” strategies is a 2010 paper by Michael Peress. His abstract is very clear, so there’s a quote:

“My results support the notion that voters abstain due to indifference and imply that candidate positioning has a large effect on voter turnout and third party voting. Nonetheless, my results indicate that the candidates can best compete by adopting centrist positions. While a candidate can increase turnout among his supporters by moving away from the center, many moderate voters will defect to his opponent.”

This paper is limited to presidential elections between 1972-2004, and using ANES survey data with post-election validated vote. I like that design, since it somewhat counteracts the problem in survey data of misreporting intent to vote. It further allows you to use respondent-reported estimates of ideology for candidates, which can tell you more about if voters *believe* them to be extreme regardless of their actual positions.

The magnitude estimates presented here are extremely variable by election, as you’d expect with a pure presidential election study. He finds that there is some effect of moderate candidates having drop-off in voting among the more extreme elements of their base, and vice versa. On the whole, he finds that moving to the extreme *does* increase turnout among base voters, but that effect is counteracted by losses of swing votes to the other party. This varies by election and situation.

I find it extremely frustrating that this paper is from 2010 and does not seem to have been replicated for modern data. Like that’s a throughline through all this research: there should be more of it. This is probably shouting into the wind.

EDIT: Literally the morning this came out, a new paper by Cutler et al got posted. It addresses the problem that “party share of total vote” can be either increased base turnout, or decreased opposition turnout, etc. It’s also using voter perception of candidate ideology, which is similar but not identical to other measures of candidate ideology. They find that extreme candidates increase the likelihood that in-party voters turn out, and also increase the likelihood that out-party voters turn out, but at a smaller magnitude. The largest positive base turnout effects are in very safe districts, which tracks.

Here’s the best summary from their paper:

“Using some assumptions about baseline turnout and in-party support, our results suggest that extremists face a penalty of about two percentage points in a district that is unfavorable to them, but gain an advantage of about 6 percentage points in districts where there are more co-partisan voters and where the effects are larger”

But does it work?????

The all important question: do more extreme candidates increase turnout among their base?

My best guess at an answer is “probably a little”. I’m not comfortable drawing a magnitude conclusion from these papers, since they’re all over the place in terms of estimate, design, and types of elections studied. It seems very plausible that there’s an increase in turnout among ideologically aligned voters when a party nominates a candidate who is further to the left (or right). What doesn’t seem to be happening is an *overwhelming* increase in turnout, or an increase in turnout in other parts of the party coalition. EDIT: It also seems possible that extreme candidates increase turnout *in safe elections* which sort of scans with real world results (see: AOC).

Do extreme candidates increase turnout among the other party?

I really have no idea. Maybe? I didn’t find a satisfying conclusion on this. It seems like turnout is super sensitive to conditions of the race (competitiveness, excitement, media coverage, spending) in a way that makes this unclear.

Is the increased turnout among the party base large enough to counteract losses of swing voters when an extreme candidate is nominated?

Probably not in most competitive elections. The exact nature of the election and district seems to matter a lot, and this is probably changing over time as well. There doesn’t seem to be significant evidence that turnout effects are larger than persuasion effects in most cases. From the Hill et al 2021 paper it seems like turnout might be more of a “thing” in certain states, which I’d love to follow up on.

Will I be updating my views at this time?

Not really. I mean, I’m updating my view on how well political science has covered this topic from “probably it’s well researched?” to “oh my GOD this needs more research”. I don’t feel very convinced that extreme candidates lead to useful turnout gains, or that they crater turnout in some way I wasn’t seeing. It seems like they’re kind of....fine, on a turnout basis. Persuasion looks to be where the real juice is.

Addendum

Thank you to my academic friends for both pointing me to papers and grabbing me PDFs. Sorry if I didn’t write about your favorite paper. No thank you to publisher websites for trying to charge me 34 dollars a paper or more.

Addendum 2: Citations

Hall, A. B., & Thompson, D. M. (2025). Revising ‘Who Punishes Extremist Nominees? Candidate Ideology and Turning Out the Base in U.S. Elections’. https://danmthompson.com/papers/hall_thompson_revised.pdf

Hall, A. B., & Thompson, D. M. (2018). Who punishes extremist nominees? candidate ideology and turning out the base in US elections. American Political Science Review, 112(3), 509–524. https://doi.org/10.1017/s0003055418000023

Adams, J., & Merrill, S. (2003). Voter turnout and candidate strategies in American elections. The Journal of Politics, 65(1), 161–189. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-2508.t01-1-00008

Broockman, D., & Kalla, J. L. (2023). Candidate Ideology and Vote Choice in the 2020 US Presidential Election. American Politics Research, 52(2), 83-96. https://doi.org/10.1177/1532673X231220652 (Original work published 2024)

Utych, S. M. (2019). Man Bites Blue Dog: Are Moderates Really More Electable than Ideologues? The Journal of Politics, 82(1), 392–396. https://doi.org/10.1086/706054

Utych, S. M. (2020). A voter-centric explanation of the success of ideological candidates for the U.S. house. Electoral Studies, 65, 102137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2020.102137

Hill, S. J., Hopkins, D. J., & Huber, G. A. (2021b). Not by turnout alone: Measuring the sources of electoral change, 2012 to 2016. Science Advances, 7(17). https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.abe3272

Hill, S. J. (2017). Changing votes or changing voters? How candidates and election context swing voters and mobilize the base. Electoral Studies, 48, 131–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.electstud.2017.06.001

Hortala-Vallve, R., & Esteve-Volart, B. (2010). Voter turnout and electoral competition in a multidimensional policy space. European Journal of Political Economy, 27(2), 376–384. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejpoleco.2010.11.003

Peress, M. (2010). Securing the base: electoral competition under variable turnout. Public Choice, 148(1–2), 87–104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11127-010-9647-0

Bonica, A., & Cox, G. W. (2018). Ideological extremists in the U.S. Congress: out of step but still in office. Quarterly Journal of Political Science, 13(2), 207–236. https://doi.org/10.1561/100.00016073